Computer-Aided Drug Design Methods An update PMC

Table Of Content

- Computational Screening Techniques for Lead Design and Development

- Drug targets

- 1. Structure-based Drug Design (SBDD)

- Associated Data

- Computational Approaches in Drug Discovery and Design

- Small molecule autoencoders: architecture engineering to optimize latent space utility and sustainability

- Database Resources for Drug Discovery

- Principal Scientist - CADD

At the early hit identification stage, the ultra-scale virtual screening approaches, both structure-based and AI-based, are becoming mainstream in providing fast and cost-effective entry points into drug discovery campaigns. At the hit-to-lead stage, the more elaborate potency prediction tools such as free energy perturbation and AI-based QSAR often guide rational optimization of ligand potency. Beyond the on-target potency and selectivity, various data-driven computational tools are routinely used in multiparameter optimization of the lead series that includes ADMET and PK properties. Of note, chemical spaces of more than 1010 diverse compounds are likely to contain millions of initial hits for each target20 (Box 1), thousands of potent and selective leads and, with some limited medicinal chemistry in the same highly tractable chemical space, drug candidates ready for preclinical studies. To harness this potential, the computational tools need to become more robust and better integrated into the overall discovery pipeline to ensure their impact in translating initial hits into preclinical and clinical development.

Call for papers - Big data and artificial intelligence for drug discovery - BioMed Central

Call for papers - Big data and artificial intelligence for drug discovery.

Posted: Wed, 05 Jul 2023 09:03:31 GMT [source]

Computational Screening Techniques for Lead Design and Development

Computer-aided design of RNA-targeted small molecules: A growing need in drug discovery - ScienceDirect.com

Computer-aided design of RNA-targeted small molecules: A growing need in drug discovery.

Posted: Thu, 11 Nov 2021 08:00:00 GMT [source]

By its ‘learning from examples’ nature, AI requires comprehensive ligand datasets for training the predictive models. With increasing library sizes, the computational time and cost of docking itself become the main bottleneck in screening, even with massively parallel cloud computing60. Iterative approaches have been recently suggested to tackle libraries of this size; for example, VirtualFlow used stepwise filtering of the whole library with docking algorithms of increasing accuracy to screen approximately 1.4 billion Enamine REAL compounds23,24. Although improving speed several-fold, the method still requires a fully enumerated library and its computational cost grows linearly with the number of compounds, limiting its applicability in rapidly expanding chemical spaces. The major types of computational approaches to screening a protein target for potential ligands are summarized in Table 2. Below, we discuss some emerging technologies and how they can best fit into the overall DDD pipeline to take full advantage of growing on-demand chemical spaces.

Drug targets

This includes structure-based virtual screening of gigascale chemical spaces, further facilitated by fast iterative screening approaches. Highly synergistic are developments in deep learning predictions of ligand properties and target activities in lieu of receptor structure. Here we review recent advances in ligand discovery technologies, their potential for reshaping the whole process of drug discovery and development, as well as the challenges they encounter. We also discuss how the rapid identification of highly diverse, potent, target-selective and drug-like ligands to protein targets can democratize the drug discovery process, presenting new opportunities for the cost-effective development of safer and more effective small-molecule treatments. The long-used traditional methodology for novel drug discovery and drug development is an immensely challenging, multifaceted, and prolonged process.

1. Structure-based Drug Design (SBDD)

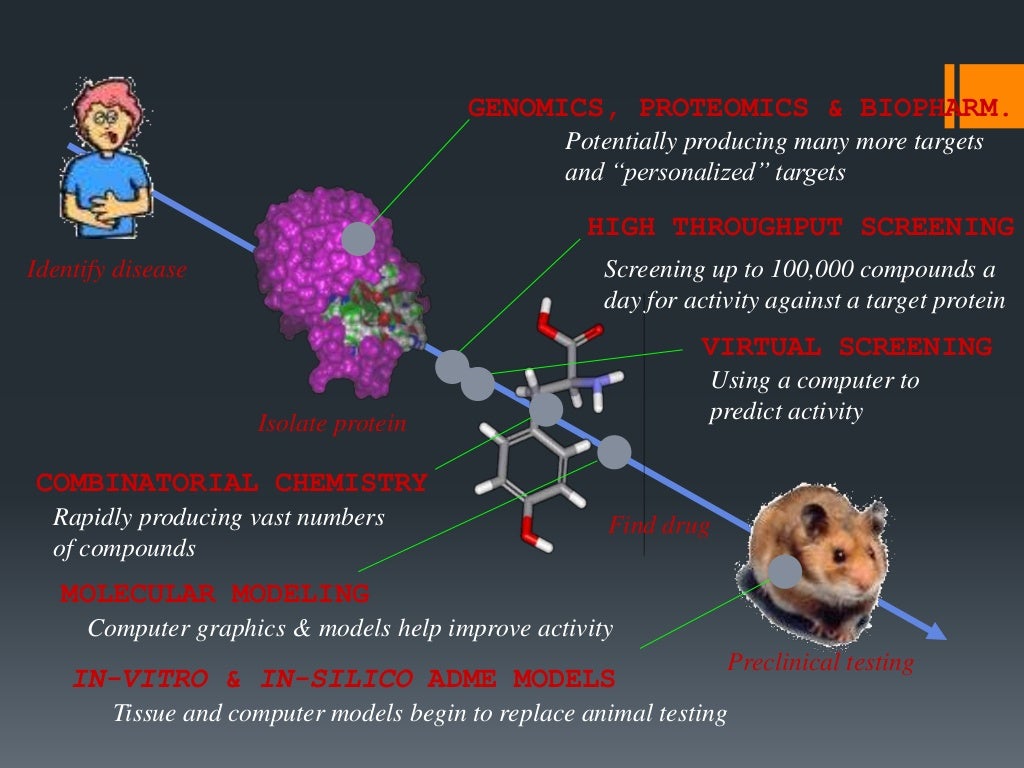

Drug discovery is a lengthy process that takes around years [1] and costs up to 2.558 billion USD for a drug to reach the market [2]. It is a multistep process that begins with the identification of suitable drug target, validation of drug target, hit to lead discovery, optimization of lead molecules, and preclinical and clinical studies [3]. Despite the high investments and time incurred for the discovery of new drugs, the success rate through clinical trials is only 13% with a relatively high drug attrition rate [4]. In the majority of the cases (40-60%), the drug failure at a later stage has been reported due to lack of optimum pharmacokinetic properties on absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME/Tox) [5]. The use of computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) techniques in preliminary studies by leading pharmaceutical companies and research groups has helped to expedite the drug discovery and development process minimizing the costs and failures in the final stage [6].

The concept of duration marks the time entry of drug molecules along with their pharmacological response. The safety rules involve the toxicity parameters which show less or no side effects on the target organisms. Henceforth all the above-mentioned factors contribute equally to the lead optimization of the drug molecule.

Al. conducted an antibiotic activity assay screen of near 2,300 chemically diverse FDA approved and natural product compounds targeting E. Deep neural network-based DL models were then trained to predict the inhibition probabilities from the chemical structures and properties of tested compounds alone. The resulting DL model was used to screen the Drug Repurposing Hub database (36) and a known c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor SU3327 was predicted to be an antibiotic targeting E.

HDAC6 is a member of the class IIb Histone deacetylases (HDACs) family and is usually found in cytosol in association with non-histone proteins [77, 78]. The implementation of CADD has been reported to result in the design of a potential inhibitor of this enzyme. In one study conducted by Goracci et al., a virtual screening approach was used to identify potential inhibitors for HDAC6, and these were then subjected to in vitro testing.

ML is also implemented in many quantitative SAR (QSAR) algorithms75, in which the training set and the resulting models are focused on a given target and a chemical scaffold, helping to guide lead affinity and potency optimization. Methods based on extensive ligand–target binding datasets, chemical similarity clustering and network-based approaches have also been suggested for drug repurposing76,77. This is an important factor in assuring the patentability of the chemical matter for hit compounds and the lead series arising from gigascale screening.

In the modern era, the process filters active ingredients passing through different phases and choosing the best candidates to enter into clinical trials. The repurposing of drugs ( drug repositioning, reprofiling, or retasking) is a way of approach to identify all the potential applications which are beyond the actual medical indication or investigational drugs(Ashburn & Thor, 2004). The concept can be referred to as drug reprofiling as uncovering new indications of the either of approved/ failed/ abandoned compounds to put in use for different diseases.

This research indicates the promising anti-leishmanial activity of Ocotillone and Subsessiline, suggesting further validation through in vitro and in vivo experiments. Although bioinformatics and molecular dynamics approaches can help to detect and analyse allosteric and cryptic pockets133, computational tools alone are often insufficient to support ligand discovery for such challenging sites. The cryptic and shallow pockets, however, have been rather successfully handled by fragment-based drug discovery approaches, which start with experimental screening for the binding of small fragments. The initial hits are found by very sensitive methods, such as BIACORE, NMR, X-ray134,135 and potentially cryo-electron microscopy136, to reliably detect weak binding, usually in the 10–100-μM range. The initial screening of the target can be also performed with fragments decorated by a chemical warhead enabling proximity-driven covalent attachment of a low-affinity ligand137.

Likewise, virtual libraries that use in silico screening were traditionally limited to a collection of compounds available in stock from vendors, usually comprising fewer than 10 million unique compounds, therefore the scale advantage over HTS was marginal. Free energy perturbation (FEP) is a higher level, computationally demanding method with increased accuracy (see Note 5) that may be used to quantify the binding free energy change related to a modification in a compound (102). The approach uses a pre-computed MD simulation of the hit compound-target complex from which the free energy difference due to small, single non-hydrogen atom modifications (e.g. aromatic –H to –Cl or –OH) can be rapidly evaluated (103). This is in contrast to the need for many simulations in which the chemical modification is introduced in standard FEP methods (102). SSFEP has the ability to give rapid predictions of binding affinity changes related to modifications and, thus, is quite useful for lead optimization (104). Despite the fact that numerous antibiotic drugs are available and have been routinely used for a much longer time than most other drugs, the fight between humans and the surrounding bacteria responsible for infections are ongoing and will be so for the foreseeable future.

Moreover, the high failure rate in clinical trials (currently 90%)2 is largely explained by issues rooted in early discovery such as inadequate target validation or suboptimal ligand properties. Although the SBDD approach has proved as a pioneer in drug designing, it has to cross the challenges that the community has to look upon. This enhancement includes screening methods, chemogenomic compounds, data improvement, quantity, quality of various tools and databases, modifying in multitarget drug structures, toxicity predicting algorithms, integrating the approach for better efficacy and compatibility. The other most sounding parameter is electrostatic interactions, entropy calculations were ignored completely. Above all, there is no single software or package that works well for particular targets and ligands including the water molecule, and probable confirmation for the target and other innovations are still need to be addressed.

Significant advancements are developments in machine learning (ML), especially deep learning (DL) based CADD algorithms (27) owing, in part, to the development of artificial intelligence (AI) methods in other areas (28). Searching for new antibiotics against established targets are still continuing where CADD methods are playing important roles. Our laboratory together with de Leeuw and coworkers are continuing the design of novel agents against bacteria cell wall biosynthesis (12, 13). In a recent study, SAR for a series of compounds that have benzothiazole indolene scaffold was pursued targeting the essential bacterial cell wall precursor molecule Lipid II (14). Using MD simulations, we predicted binding free energies and binding modes of Lipid II binders and gained atomic details on the interactions between designed molecules with Lipid II, information that will be useful for further development of antibacterial therapeutics. Schematic comparison of the standard HTS plus custom synthesis-driven discovery pipeline versus the computationally driven pipeline.

However, CADD methods have some limitations such as lead molecules derived from the virtual screening process that still need validation through preclinical and clinical assessments before market approval [167]. The fact that the molecular mechanism studies underlying the disease pathogenesis of COVID-19 are still underway, and the existence of bias and imbalance in the limited data available can have a major impact on the prediction accuracy of CADD methods such as artificial intelligence [168]. Ligand-based drug design is another widely used approach used in computer-aided drug design and is employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target receptor is not available. The information derived from a set of active compounds against a specific target receptor can be used in the identification of physicochemical and structural properties responsible for the given biological activity which is based on the fact that structural similarities correspond to similar biological functions [77]. Some of the common techniques used in the ligand-based virtual screening approach include pharmacophore modeling, quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs), and artificial intelligence (AI).

Comments

Post a Comment